Francis Boscoe, Founder Pumphandle LLC

It is not hard to find examples of pundits who have publicly declared that the forty-some year-old War on Cancer has been lost. “Losing the War on Cancer” was the subtitle of a well-received book.1 Scientific American called it a “bust.”2 It’s not just bloggers and reporters: the consensus among cancer researchers and clinicians at the World Oncology Forum a few years ago on this question was solidly negative.3 Twenty years of telling people at dinner parties what I do for a living has led me to believe that the prevailing view is one of doom, and that things will only get worse. Restyling the “war” as the Cancer Moonshot has not silenced the critics. A New York Times op-ed penned in response was bluntly titled “We Won’t Cure Cancer.”4 To the Cancer Moonshot’s credit, the stated goal was not to cure cancer, but rather to accelerate a decade’s worth of progress into five years, but this does not lend itself as easily to catchy headlines.

However, the data that we so painstakingly collect suggest precisely the opposite. Cancer mortality in the United States has been dropping steadily for a quarter-century, driven by advances in treatments, early detection, vaccination, and reduced smoking rates. It is true that the rate reduction has been slow — 1 to 2 percent per year — which may contribute to some of the misperception. But cancer mortality overall is down 26% from its 1991 peak, and, should this trend continue, would reach half the 1991 level in 2046. That’s a 55-year time span, longer than most professional careers, too slow to recognize easily.

What’s more, people tend to mix up incidence and mortality, and it’s true that incidence has gone up for many cancers. But this is largely a consequence of technology that allows us to find nodules and lesions on a millimeter scale that are of limited clinical importance. It’s likely that we know more people with cancer than our parents would have known, but that is quite different than knowing more people who have died from it. People are also more public about their cancer diagnoses than in the past, further amplifying this effect.

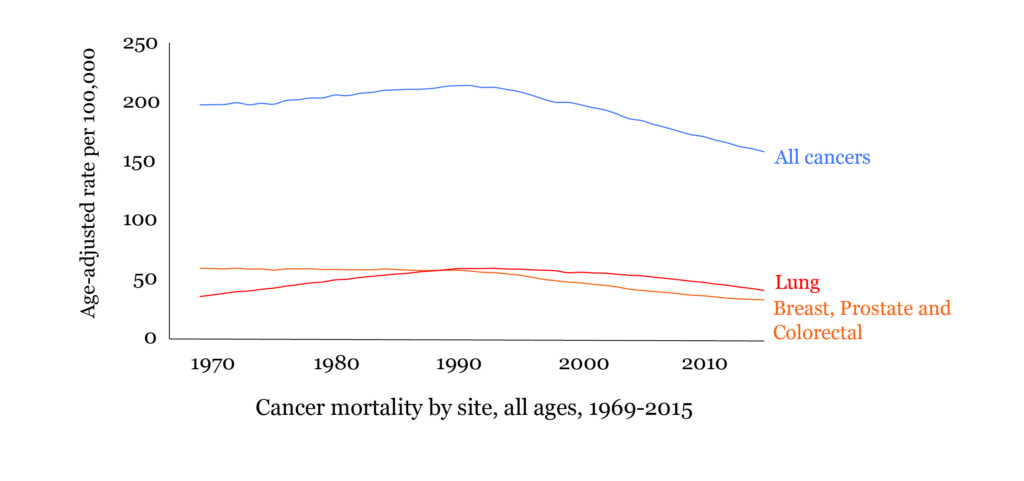

Some who acknowledge the decline in mortality nevertheless refuse to credit the medical establishment, claiming it is only a consequence of people smoking less than they used to. This graph shows the age-adjusted mortality rates for all cancers combined, lung cancer, and the combination of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, together the four most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States. Note that the mortality rates for breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer have declined much more steeply — since 1991, about 2.2% per year versus 1.5% for lung, even though none are strongly associated with smoking.

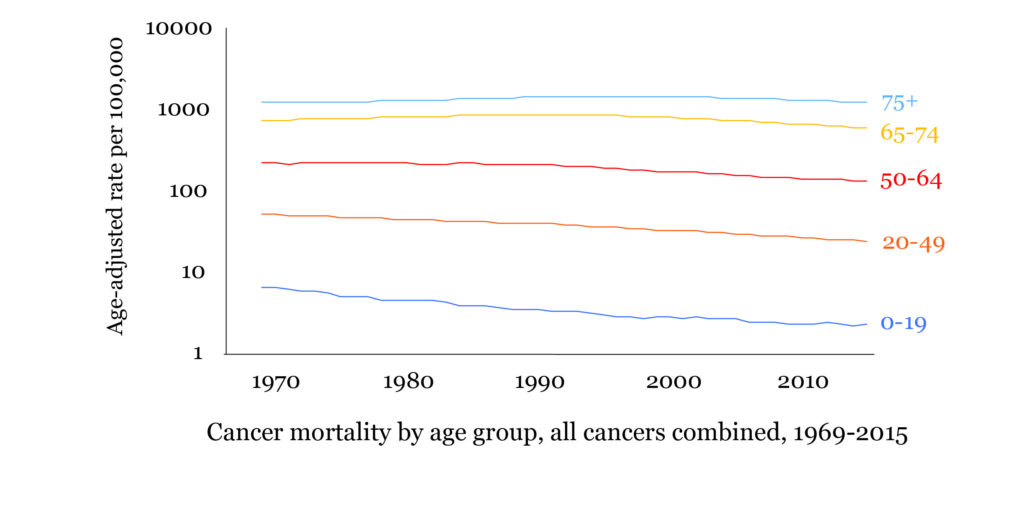

Viewing the data by age group is also revealing. The graph below shows trends for five different age groups, presented on a logarithmic scale for clarity. Here we see that the reduction in mortality is proportional to age, with children seeing the sharpest drop and the elderly barely budging at all. If you are above 75, then your perceptions about cancer may not be too far off: cancer mortality among your peers is about the same as your grandparents would have found it to be when they were your age. But that ignores the substantial improvement among your children’s and grandchildren’s generations.

Notably, mortality among those under age 50 have been dropping for a half-century. Even the earliest years of the War on Cancer saw some successes in this age group. Children up to age 19 died at a rate of 6.6 per 100,000 in 1969 and that number had sunk to 2.3 in 2015, a 65% reduction.

Complicating this analysis is the fact that cancer is not one disease, but hundreds. That they are all lumped together is a legacy of disease classification systems developed in the nineteenth century. The incremental progress we see among all cancers combined is consistent with varying rates of progress for various diseases. For some types, there have been virtually complete cures (Hodgkin lymphoma, cervix) and for others there has been almost no progress at all (brain, pancreas). Clearly something about the cancers that tend to afflict younger people has made them more amenable to cure.

I was speaking with a urologist the other day who referred to prostate cancer as a “generational disease.” By this he meant that the treatments and practices in place today are probably working, but it might take generations to really feel the impact. I think “generations” is putting it too strongly, but he is correct. Certainly the pace of progress is too slow for our liking — I know people today who will almost certainly die from their cancers, the required breakthroughs and societal changes still decades away — and this brings me great sadness. And yet the data quietly reveal that we are already further along than we realize.

References

1Horgan J. 2014. Sorry, but so far War on Cancer has been a bust. On line: https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/sorry-but-so-far-war-on-cancer-has-been-a-bust. Accessed November 20, 2018.

2Leaf C. 2013. The truth in small doses: why we’re losing the War on Cancer – and how to win it. New York: Simon & Schuster.

3Hanahan D. Rethinking the War on Cancer. The Lancet 2014; 383: 558-563.

4Breivik J. We won’t cure cancer. New York Times May 27, 2016: A21.